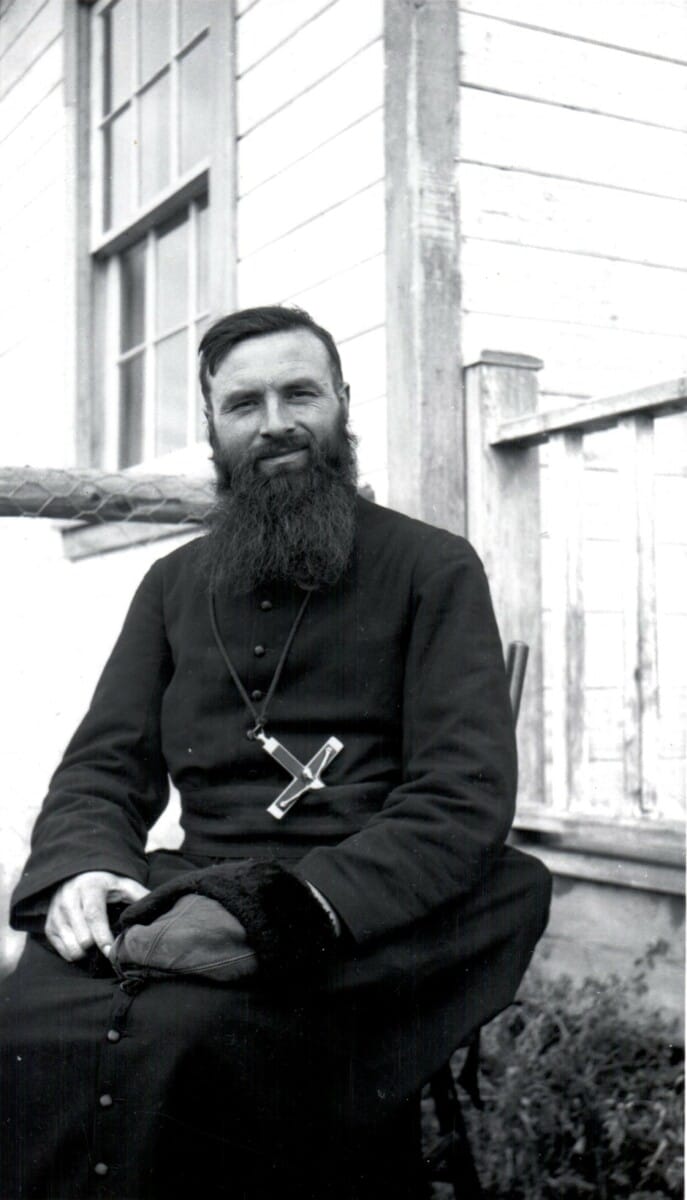

Memories of Fr. Mariman

The legacy of missionary priest continues to endure in the Canadian north

There have been many missionary priests that have served and shaped the missions of the archdiocese, leaving behind a lasting and enduring legacy.

A name that often stands out amongst the most northernly Indigenous communities of the archdiocese is Fr. Cesaire Mariman, OMI, who served the north from 1935 until the late 1980s. This missionary Oblate from Belgium is remembered for the grottos he built in Eleske and Meander River, for the pilgrimage he started amongst the Child Lake Nation, and as a missionary who mastered many Indigenous languages, particularly Beaver and Chipewyan (Dene). This mastery led him to translate both the Gospel of Matthew and Mark into Beaver, and to develop a grammar book of the language.

But where his legacy is perhaps most enshrined is simply in the cherished memories of the people he served. His life continues in the words of those who still talk about him today and still carry on the Faith he shared with them.

Marian Enfield of Meander River is particularly a living testimony to the enduring legacy of Fr. Mariman. Marian was only 14 years old when the priest passed away in 1989, but the impact he made on her life will be everlasting. To this day he continues to be a subject for fond discussion and remembrance amongst the peoples of Meander River, and Marian notes that many people refer to Fr. Mariman today as “our saint”.

“Everybody knew him and everybody respected him in this community, and in the communities around this area,” said Marian. “He was always visiting with people. Whenever we talk about him, we just feel so happy. His memory never died. I still always talk about him.”

As a child, Marian would spend her days helping Fr. Mariman around the church and at his small home that neighboured it. Because his house in Meander River was so close to their school, Marian and her siblings would sometimes sleep in the upstairs of his home before early morning field trips. During the school year, Fr. Mariman would be in the classroom almost every morning to pray the Our Father with students and most summers he would host a Bible camp for children at the grotto he built.

Even in the times when he was strict with the children, always ensuring they paid attention during Mass and wore the proper clothing, he is still remembered with great fondness.

“Some people when they go to church now, they may say that the priest is strict. But I always say, ‘Well, remember how strict Fr. Mariman used to be. So you know strictness is good,” said Marian.

The two shrines and grottos dedicated to the Blessed Mother, built by Fr. Mariman’s own hands, are especially a testament to his dedication to the communities of Eleske and Meander River.

90-year-old Mary Francis of Eleske can still recall when Fr. Mariman and her grandfather built the grotto that stands in Eleske today, which remains the site of their annual pilgrimage.

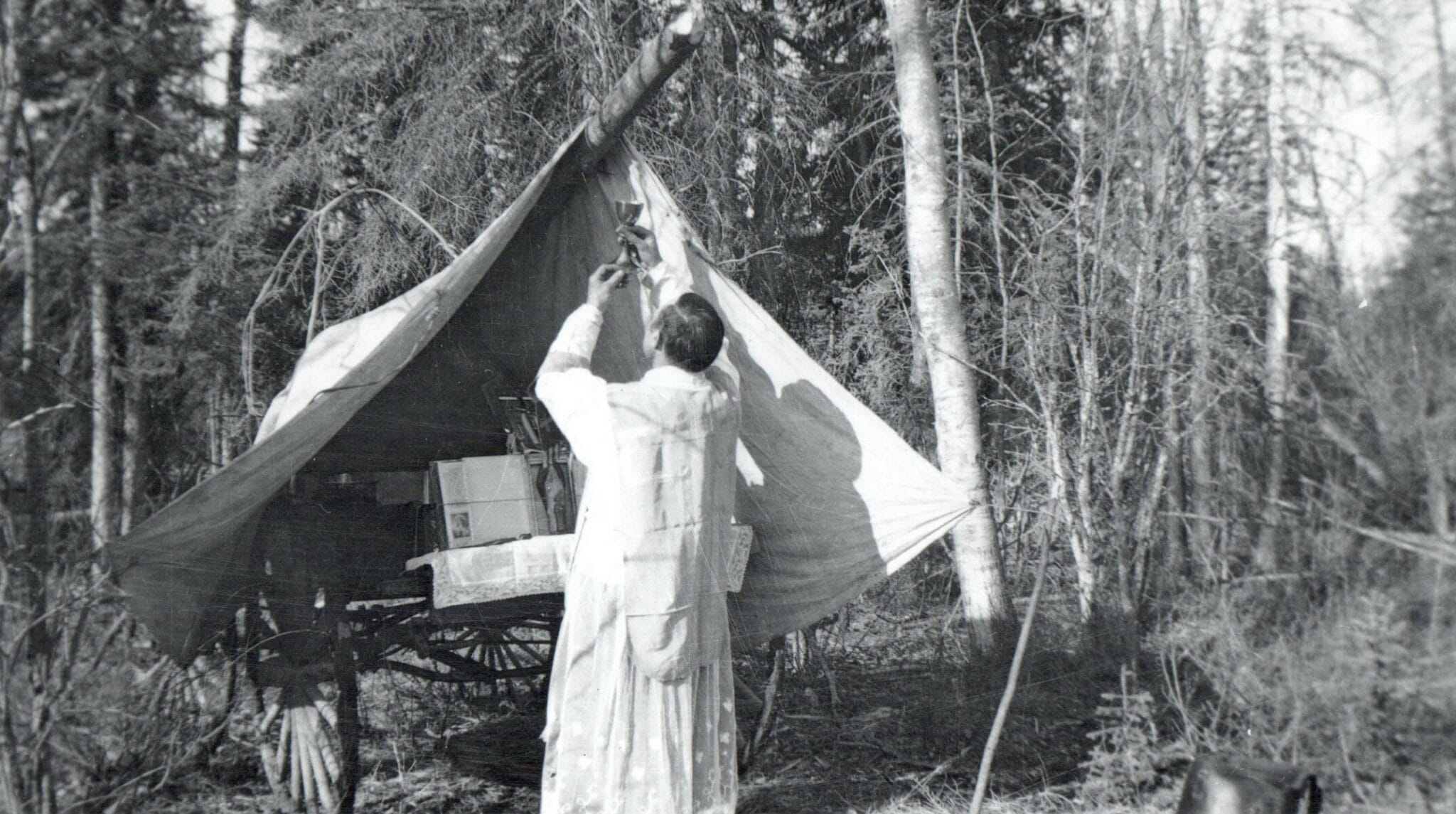

Though it was now many decades ago, Mary can even recall the name of Fr. Mariman’s horse “Chonky”, who pulled the wagon he would ride in on whenever he came through the Beaver reserve to celebrate Mass.

“He was a good priest. There was no priest like him. Maybe he was the best priest we ever had,” said Mary. “He was good to everybody. He built our grotto; he talked our language. The people were surprised he could speak the Beaver language so well.”

One peculiar memory that was noted by both Mary Francis and Marian Enfield is Fr. Mariman’s curious love for eating dandelions.

“He used to just pick the dandelions and eat them,” said Mary. “He said they were good for you; they had a milk in them that was good for you.”

Fr. Mariman’s close friendship with Mary’s grandfather was a key help in his ability to learn the Beaver language so well, and he was also the priest’s most trusted helper in keeping up the church and maintaining the grotto.

“My old grandpa would be with him everyday,” Mary said with a laugh. “Whenever he wanted help with something, he would go and get my grandpa. He would help with chores around the church, they made a little narrow bridge with gravel to cross the river, and him and my grandpa would haul stones by wheelbarrow to build the grotto.”

Mary was at the first annual pilgrimage in Eleske on those grotto grounds, back in the late 1940s, and she still travels there each year, to pray before those same grotto stones hauled over by Fr. Mariman and her grandfather.

It is on these very grotto grounds that Fr. Mariman was laid to rest. Rather than return to his native lands in Europe, he asked to be buried amongst the peoples he served – it was with them that the missionary priest found his home and resting place.

The cross and gravestone above his body are an abiding reminder of how much he was devoted to the area.

“I used to ask him, Father, where did you come from?’ He’d say, ‘I came all the way from Belgium’. I could hardly imagine where that was,” said Mary. “Eventually he told the bishop, ‘When I leave this world, I want my body to be laid amongst the people here. I want to be laid where I worked.’ So his grave is still here – at the church cemetery where he asked to be buried.”

Much like the pilgrimage and grotto, Fr. Mariman’s grave continues to be visited by the people who are loyal to the priest that dedicated his life to serving them. Donna Yakinneah of Meander River travels to the cemetery grounds in Eleske almost every year, just to see his grave and pray for the dearly missed priest.

“Many people from Meander River go to the Eleske Pilgrimage especially to go see his grave,” said Donna. “And my mom always told us wherever we want help, to pray to Fr. Mariman. That’s why we go to his grave every year in Eleske.”

“Even when I go to the grotto now, I’ll drink form the spring water and I pray that Fr. Mariman will keep our community safe,” Marian added. “And maybe that’s why I find our community of Meander River, it’s not as crazy here as in some other First Nations reserves.”

…

Alongside the grottos and pilgrimage he founded, Fr. Mariman’s dedication was particularly reflected in his passion for learning the languages of the Indigenous he lived amongst. He especially knew well the Beaver Indigenous language. In his translations of the Gospel into Beaver, he added visual drawings to each of these translations to further help his readership understand its meaning.

In an archived interview with Fr. Mariman, given just a few years before his death, the priest gave a detailed overview of the differences in grammar and syntax in a variety of Indigenous languages such as Beaver, Chipewyan (Dene) and Cree, revealing just how vast his expertise was. He also noted the work done by previous Oblate missionaries like Fr. Albert Lacombe and Bishop Emile Grouard who left behind their own texts on how to understand each of these languages. He particularly drew from a collection of homilies by Fr. Albert Lacombe written in Cree.

In this same interview, Fr. Mariman also reflected on the tragic ways that the Beaver language was dying out amongst its own people. He noted that people often preferred that the priest speak to them in English than in their own Native tongue, which was becoming increasingly distant to them.

One person who distinctly remembers Fr. Mariman for his fondness of language and linguistics is Rosemarie Willier.

She grew up in Hay Lakes, a Dene Indigenous community near Fort Vermillion that Fr. Mariman also served. The priest had spoken to her in his later years of the curious commonalities he had discovered between the languages of the Beaver and Dene and some of the Scandinavian languages of Europe.

“He told me that his own language was very similar to that of Beaver Indian. He even said that some of the words were almost identical,” Rosemarie recalled.

This intimate grasp of their language reflected how dedicated Fr. Mariman was, and he remained a constant defender of the Indigenous peoples.

This is only an excerpt. Read the full story in the July-August 2024 edition of Northern Light