‘This is how it was’

Senior who altar served at cathedral’s consecration Mass reflects on its more than 70 year history

On the drive into town from Highway 2, the St. John the Baptist Cathedral stands high above the small community of McLennan. At its peak, the statue of John the Baptist, the great prophet of the New Testament and the cathedral’s namesake, oversees the area.

Long time McLennan resident Paul Dubrule walks down the aisle of the cathedral, noting that the pews where Paul sits today are the same ones his family sat in at the cathedral’s opening consecration Mass in 1947, and when he and his wife were married there many years later. The age of the pews is easily noticeable in their straight 90-degree backs and hardwood kneelers.

“When we first moved in here, this is how it was,” the 89-year-old recalled, looking over the church interior of today. “It’s been painted over a couple of times here and there but that’s it.”

In terms of the pews, altars, paintings, statues and tinted glass windows, over the years not much has changed within the walls of the St. John the Baptist Cathedral – but the same cannot be said for the world around it.

At the time the cathedral began construction in 1945, McLennan was an area of growing development for northern Alberta, as the train and railway station established there brought much activity for commercial and passenger travel. There was an air of certainty that McLennan would grow to be a central hub for the region. It was this air that influenced the archdiocese (at this time, the Vicariate of Grouard) to build its chancery office and cathedral in McLennan.

A decisive factor in the development of northern Alberta in this period was the railway system. It brought much employment, was crucial to the transportation of crops and other materials, and, before the construction of highways and the introduction of vehicles, the train was the technology of choice for people needing to travel extensive distances. But the railroad had by-passed Grouard, where the vicariate had first established its chancery, and soon McLennan took hold as the ideal destination for its headquarters and cathedral.

“The railroad was the main reason they moved,” said Dubrule. “It went from Edmonton, on to McLennan and Hines Creek, and north to Peace River and south to Grande Prairie and Dawson Creek.

“In those days it was the main way of travel, not many people had vehicles and there were mostly only dirt roads. With the railroad division built here, they figured McLennan would grow to be the area’s main distribution centre.”

The chancery office was built first – completed in 1942. It’s a vast four level building with an extensive library, multiple bedrooms and bathrooms (as it often housed many Oblate priests and brothers), offices, kitchen, conference rooms and extensive archives. When the chancery opened, Dubrule remembers children from the parish were asked to help carry over the sacramental records from the initial small church in McLennan over to the new building.

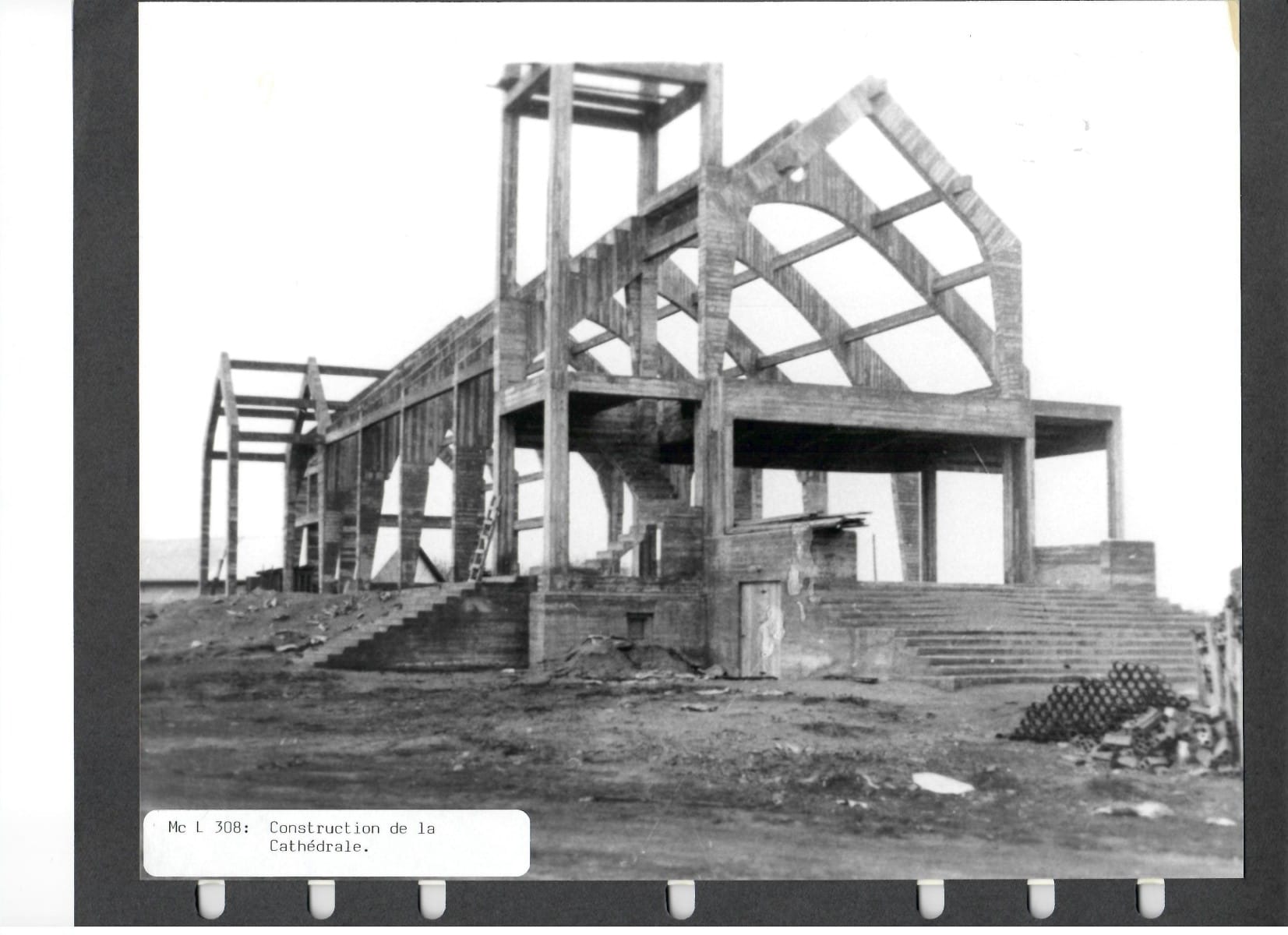

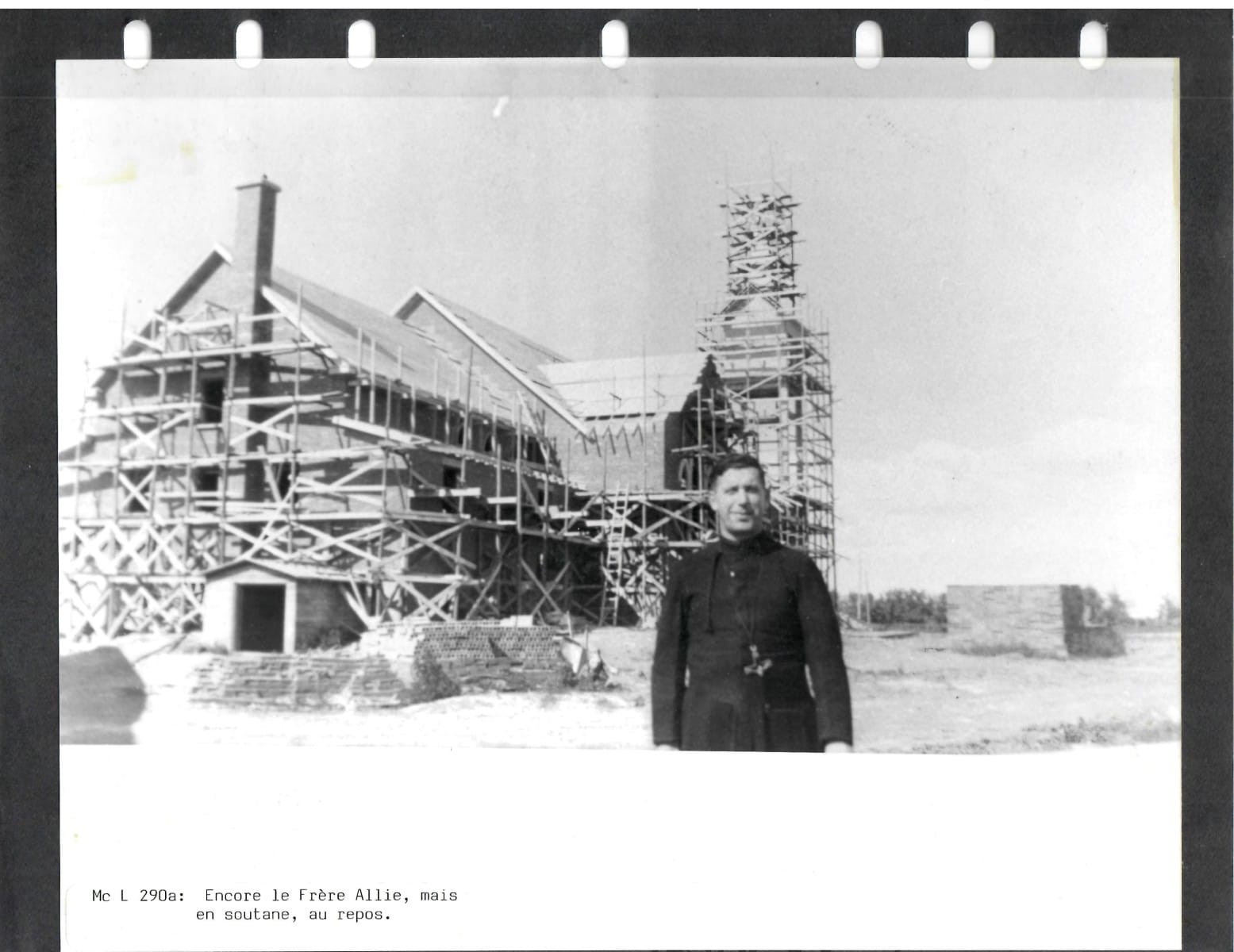

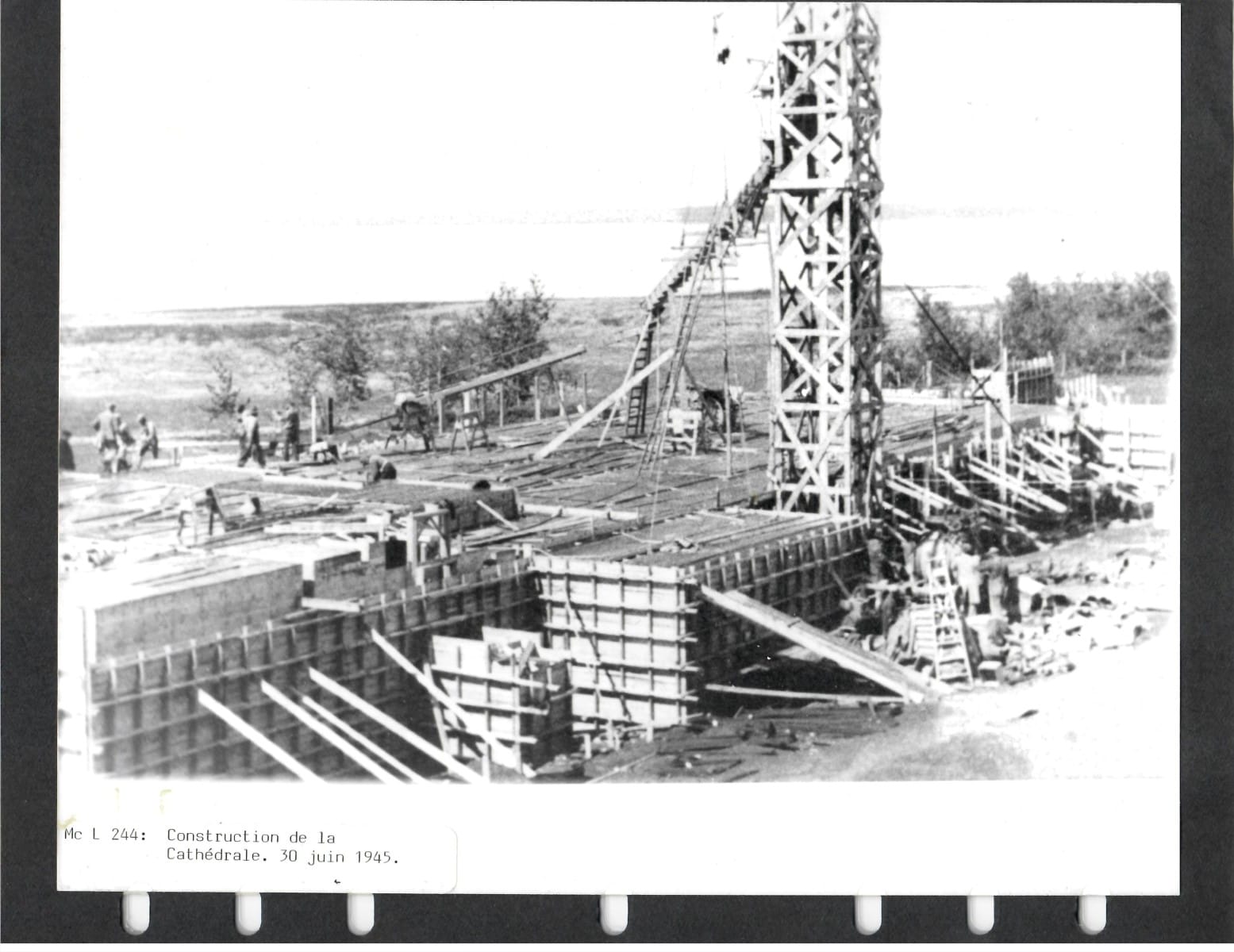

Construction on the cathedral began around 1945. It was to be made almost entirely out of bricks and concrete, built by both locals and hired workers from outside the area. Dubrule recalls that one of his brothers had a truck and hauled in several loads of concrete for the cathedral build. Without today’s heavy machinery, the concrete was mixed and brought into the construction site almost entirely by wheelbarrow and lifted by a pulley system.

Considering he was only 13 when construction began on the cathedral, Dubrule’s memories of this period are scattered and vague.

His sister was married in 1946 in the old McLennan church, but he remembers they stopped by the under-construction cathedral after the wedding. That same year, the midnight Mass on Christmas was celebrated in the basement of the cathedral, its upstairs still on its way to completion.

The cathedral build was finally completed in late 1947, its consecration Mass celebrated that October.

“It was something that took three years to build, so there was a gradual excitement, and when they did the consecration and blessing of the church that was a big event,” he said. “I got to altar serve at that consecration Mass and priests from all around the vicariate came for it.”

After the cathedral and chancery were completed, McLennan soon became a center for religious life also.

Along with the bishop, rector and vicar, several religious brothers were typically at work and staying in McLennan’s chancery building, some of whom handled things like bookkeeping and archiving. Religious sisters also subsequently came to the area to work. The Sisters of Providence worked in the local hospital, school and later in McLennan’s nursing home.

McLennan was a dominantly French community at the time the cathedral was built, but there were also many English Catholics in the area. The parish celebrated a bilingual Mass from its very beginning and continues to in some fashion today.

By 1950 McLennan’s population was around 1,100, but Dubrule says it was not unusual to have such a big cathedral in a small town, because the church was always full.

“We had two Masses every Sunday back then, and the Church was filled each time. At midnight Mass the cathedral was packed, so it was not strange,” he said.

But as the years went on, the vision of McLennan as a central hub and distribution centre for the area never did come to fruition. The highway system and influx of vehicles slowly eliminated passenger train travel. The development of oil and gas ended up being the defining economic factor for the region, which has today made Grande Prairie the most populated city in the archdiocese.

“The town of McLennan was established in the same decade as Grande Prairie,” Dubrule recalled. “Grande Prairie grew and Peace River grew, but for various reasons this area did not.

“Some people feel if there had been better governance at the time things might have been different. Peace River has a grocery distribution centre, and if there had been more efforts to build that in McLennan it would have helped a lot. That’s just the way I look at it.”

In earlier days, Dubrule notes, the trains and railroads also provided much more employment than they do now.

“Back then each train would have two engineers, two firemen, a conductor and now the train can take off with only one person operating it,” he said. “That’s something that led to less employment here and the population has kept going down.”

The population of McLennan today is around 750. In 2014, the archdiocese relocated its chancery office to Grande Prairie. Last year, the grocery store in McLennan shut down and their hospital is now down to a single doctor.

The archdiocese’s cathedral remains in McLennan, and Archbishop Pettipas still celebrates Mass there one Sunday every month.

The multi-story chancery building, with its multiple offices, bedrooms and other facilities, today is the rectory of one priest – McLennan’s pastor Fr. Eucharius Ndzefemiti. The archdiocese also continues to use this building for various things.

The days of being an adolescent altar server are long gone, but Paul remains intensely involved with the cathedral today – as a member of the parish council, of which he was the president for many years, and he also helps with general maintenance and ensuring the sacristy has all necessary items. When the lights need changing on the high arches of the cathedral ceiling, Paul is often the one who climbs up into the attic to walk along the scaffolding and change the light bulbs.

“People depend on me. It’s always, ‘Paul we need this’,” he said with a laugh. “I don’t know why that is. I guess I just can’t say no.”

There is much care involved in maintaining a cathedral the likes of St-Jean-Baptiste. But now in his late 80s, Paul says he is ready for retirement and for a new person to take over these duties. However, as it is in many smaller communities of the archdiocese, there is uncertainty towards who will fill the pews and fill these roles in the next generation.

“What will happen in the future we don’t know. The young people are not going to church as much, and we’re just barely making ends meet right now. We rely a lot on donations and volunteering to keep up,” he said. “A lot of the older people in the community are worried about the cathedral for sure, even now it’s too big for us.”

Whatever the future holds, within its tinted windows, high arched ceiling and brick walls, the St John the Baptist Cathedral remains a landmark for the McLennan community.

For Catholics of northwestern Alberta, it remains the central heart of our archdiocese. Each Holy Week the cathedral hosts the Chrism Mass, bringing together priests and parishioners from across the region to celebrate Mass and bless the sacramental holy oils used in all of our churches for the celebration of sacraments. Last winter, the McLennan cathedral and rectory hosted a retreat with nearly 25 young adults from as close as High Prairie and as far north as Fort Vermillion.

Engraved on the church’s cathedra (bishop’s throne) is the image of the pelican piercing its own chest with its beak to feed and nourish its young. Since the early Christian centuries, this image has been used as a symbol of Christ, sacrificing Himself for mankind. It is thanks in part to the personal sacrifice of locals like Paul Dubrule that the St John the Baptist Cathedral also remains a source of nourishment for the archdiocese, pouring out sacramental graces and continuing a cherished history.