Bringing history to light

Archdiocese has high hopes that Indian Residential Schools project will be a positive step towards reconciliation

Kyle Greenham

Northern Light

Archbishop Gerard Pettipas can still recall the painful yet heartfelt and hopeful moments of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s seven national events.

“These were amazing events,” Pettipas recalled. The archbishop was the president of the Corporation of Catholic Entities (named CEPIRSS) during the commission, which ran from 2008 to 2015. CEPIRSS represented 50 religious groups, dioceses, congregations and religious orders who had at one time worked in Indian Residential Schools.

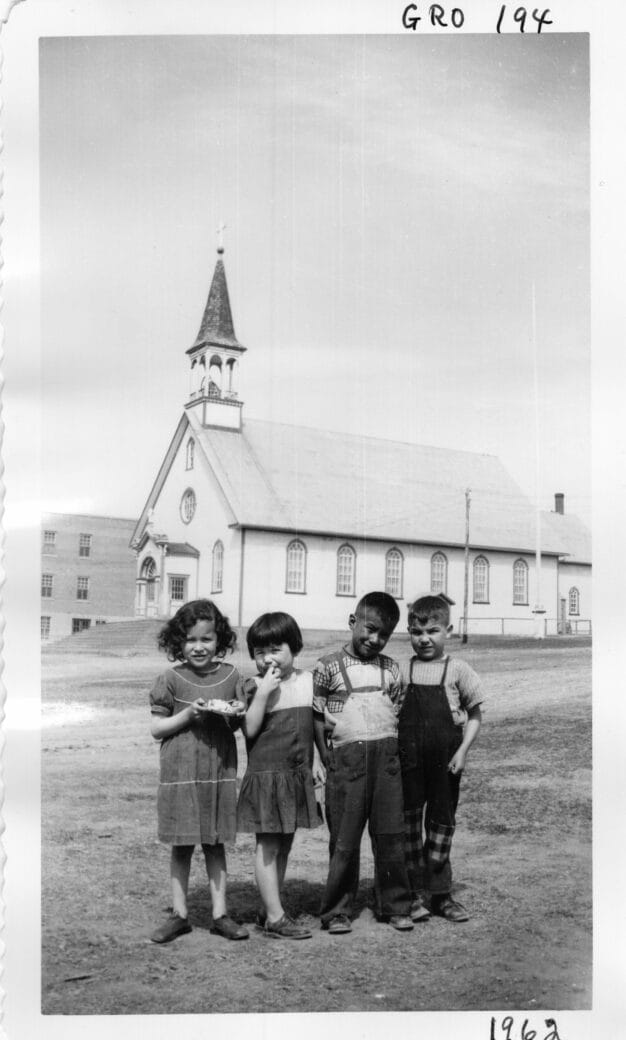

“They were painful in the sense that many of the stories told at these events were deeply painful stories, they were not happy stories,” Pettipas continued. “However, mingled with that were a lot of joyful moments. One of the services the churches were asked to provide was photo albums for these events, and to make copies of these photos for any former students that asked for them.

“Many people went through these albums and if they saw themselves, or a friend they had at school, they were delighted. Many of them were seniors who had never had a picture of themselves as children. They cherished this. I found this to be a very pleasant experience to be in this area of the TRC events.”

It was these moments that first sparked the work of the Archdiocese of Grouard-McLennan to look into a Indian Residential Schools photo project, which has now made more than 3,000 images from the six residential schools and missions that operated in the region publicly available. Alongside the images being available on the archdiocesan website, the archdiocese is also preparing photo albums for the Indigenous communities in the region.

“We say that a picture is worth a thousand words, so for somebody to have a picture of themselves from a previous age, with people they cared about and loved – this is valuable to them,” he said. “And to me this was one of the most positive elements of the TRC events, and having this gallery now on our webpage, it invites people who had gone to these schools to go through these images to see if there’s something there that will connect them to the past, that they may want to hold on to.”

The idea was made a reality thanks to a Library and Archives Canada’s announcement in 2016 for new grants in their Documentary Heritage Community Program. Upon hearing of this news, the archdiocese hoped the funding could provide an opportunity to digitize a significant number of the archdiocese’s archived photos, and, most importantly, address healing and reconciliation through the publishing of photos related to Indian Residential Schools.

The archdiocese applied for the grant three times before they were finally approved in late 2018. The project limited itself to 6,000 images related to the Indian Residential Schools and the surrounding missions. Six schools operated within the missions of the region – Wabasca, Joussard, Fort Vermillion, Grouard, Sturgeon Lake and Chateh (Assumption).

Project lead Lauri Friesen determined what kind of software and equipment were needed for the project, including a scanner, computer, backup external hard drives and DVDs. She also decided which of the 6,000 photos would be uploaded online and sent to the area’s Indigenous communities. Her criteria was to mainly focus on images that featured people, had historical significance and were the most evocative for viewers. Many of the 6,000 photos were also doubles or multiple shots of the same image, and these additional copies were archived but not published.

From May to August of 2019 the actual digitizing and cataloguing of the photos began. As part of the grant funding, the archdiocese was able to hire two students to work full-time over that summer – Emily Elsenheimer and Patrick Davis.

By the time Emily and Patrick got involved, the photos were already sorted according to the six different schools and missions they were a part of. Their jobs were to cut the photos, create or rewrite bilingual descriptions for the images, and then scan them and catalogue them into the digital archives database.

They worked on the project for three months, working from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m., Monday to Friday.

“We would switch roles every other day, because it could get very monotonous,” Emily said. “Scanning them digitally also took up a lot of time, as did individually dating and filing each one.”

For adding descriptions to the images, many of the photos already had details written underneath or on the back of them. For those that did not already have descriptions, the photos were analyzed based off of the surrounding buildings or which priests or sisters were in the images, and from there many of the images were able to be dated, at least by decade. They then catalogued these descriptions with one major finding aid document for each school.

“Typically we would pinpoint within a ten-year range, but sometimes we would be able to get a specific date,” said Elsenheimer. “Like an archbishop came to visit at this specific date, so any photos related to that we would know how to date them. The photos were also already numbered and usually archived chronologically and that helped with the dating.”

The experience also gave Emily and Patrick the unique opportunity for an intimate look at this important history of northern Alberta.

The full story with many more photos will be in the November edition of Northern Light